Thursday 8th January 2026 The Grand Tour of Ice Giant Aurorae

JWST’s transformational observations of Uranus and Neptune

Professor Tom Stallard, Northumbria University (speaking remotely from Northumberland)

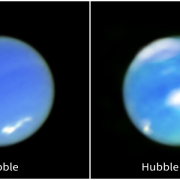

The image is the first Neptune auroral observation since Voyager, and the starting point for our observations. At the left, an enhanced-color image of Neptune from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. At the right, that image is combined with data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

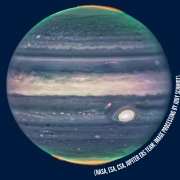

When the Voyager II spacecraft flew past Uranus and Neptune in 1986 and 1989, respectively, it reveals a strange new type of world, somewhere between the Gas Giants of Jupiter and Saturn, and rocky terrestrial planets like Earth and Mars. These worlds, made from ices for most of their depth, but with deep atmospheres, were unique in their magnetic fields. Unlike Earth’s ‘bar-magnet’ like magnetic field (and the magnetic fields of Mercury, Jupiter and Saturn), these worlds had strangely complex magnetic fields, with four poles, perhaps even eight, magnetic poles (2 north and 2 south). Though unlike anything else in our current solar system, these fields seem to be very much like the fields that Earth itself produced during past magnetic field reversals, making them of great interest in understanding both Earth’s past and the many variant planetary magnetic fields around other stars.

But, since Voyager, these planets have been hidden from view. A handful of Hubble Space Telescope observations have weakly sampled the UV aurora of Uranus when they are strongest, but we have never observed the aurora of Neptune in the past 35 years. JWST has changed all that – this incredible telescope can not only show these aurora at the edge of our solar system, we instead see brilliant views of both the aurora and the entire surrounding upper atmosphere, laying out not only aurorae but also the magnetic fields across the planet. So far we have observed Uranus twice and Neptune once.

In November 2025 and January 2026, we are undertaking a Grand Tour of Neptune then Uranus. Watching these planets for an entire month, we will see how the aurora of these worlds change across a solar day, as the Solar Wind, filled with regions of compressed and rarefied wind, reaches and distorts the magnetic fields of these worlds. In doing so, we’ll massively improve our understanding of the aurora of Uranus, and for Neptune, we will literally increase the total number of auroral images ten-fold. It is the largest JWST planetary observation ever made: we will be revealing the latest images and talk about what we think we’ve discovered so far.

Professor Tom Stallard, Northumbria University

Tom Stallard is a Professor of Astrophysics at Northumbria University, UK. He is a leading planetary astronomer in the UK, who currently has the largest number of JWST hours of any planetary astronomer in the world. In 2019, he was awarded the

Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) Chapman medal for his research into planetary aurora. He has shared his astronomy with the wider public in a range of ways, including RAS ‘live from the observatory’ events. He was presented with the title ‘Hoku Kolea’ by the Mauna Kea observatories for his work in public engagement.

A video recording of the this talk will be available here.